In the wake of the massive storms that devastated Puerto Rico, Florida, and Texas in recent months, communities begin to rebuild. For many, rebuilding is only possible thanks to a payout from the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP).

But for all the homeowners the NFIP buoys, the program itself barely stays afloat. As the deadline to reauthorize the program quickly approaches – with the House passing a bill this week – federal lawmakers need to decide whether to throw more money into the leaky program, or seriously repair the NFIP.

Why do we have the National Flood Insurance Program?

In the late 1960s, the federal government recognized that disaster relief placed an increasing burden on resources. So, Congress decided to require property owners in flood-prone areas to purchase flood insurance. In considering the requirement, Congress understood that “many factors have made it uneconomic for the private insurance industry alone to make flood insurance available to those in need of such protection on reasonable terms and conditions.” Lawmakers established the NFIP, which insures more than 5 million properties today.

How does it work?

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) administers the program and creates flood maps. These maps designate areas that are expected to experience a “100-year flood event,” meaning each year, they face a 1 percent or greater chance of flooding. Local governments must work to reduce the risk of future floods – through things like limiting development and requiring building standards – in order for NFIP to offer insurance in their communities.

With few exceptions, homeowners in FEMA flood zones are required to purchase flood insurance. FEMA oversees the program and the federal government is on the hook to pay accepted claims, but the day-to-day sales, writing, and management of claims is handled by private companies. The maximum coverage limits of standard flood insurance policies offered by the NFIP are set by law, currently up to $250,000 for single-family homes and an additional $100,000 for the property’s contents.

What does it cost?

The median flood insurance premium is about $520 a year – but it varies widely, with most policies costing between $420 and $1,330 a year. The price of flood insurance is supposed to be based on how likely a property is to be damaged by floods – this is considered “actuarially sound.”

However, law directs FEMA to not charge premium prices that reflect the true risk to properties built before 1975 or before the area’s first published flood insurance rate map. Premiums for these properties will eventually reach actuarially sound premiums, but the pace of the rate hikes is the subject of current political debate. Another form of grandfathering in the NFIP is that property owners can keep their old insurance rate even when their property is remapped into a higher level of flood risk, where they’d expect to pay a higher rate.

How big of a deal is the NFIP? Is it used often? And where?

We’re so glad you asked, we actually looked into that.

Our research shows homeowners historically buoyed the most by flood insurance live in a small number of places with high-value homes. In fact, since 1978, just twelve counties are responsible for a third of flood insurance claims, and the median home value in those counties is 34 percent higher than the national median home value.

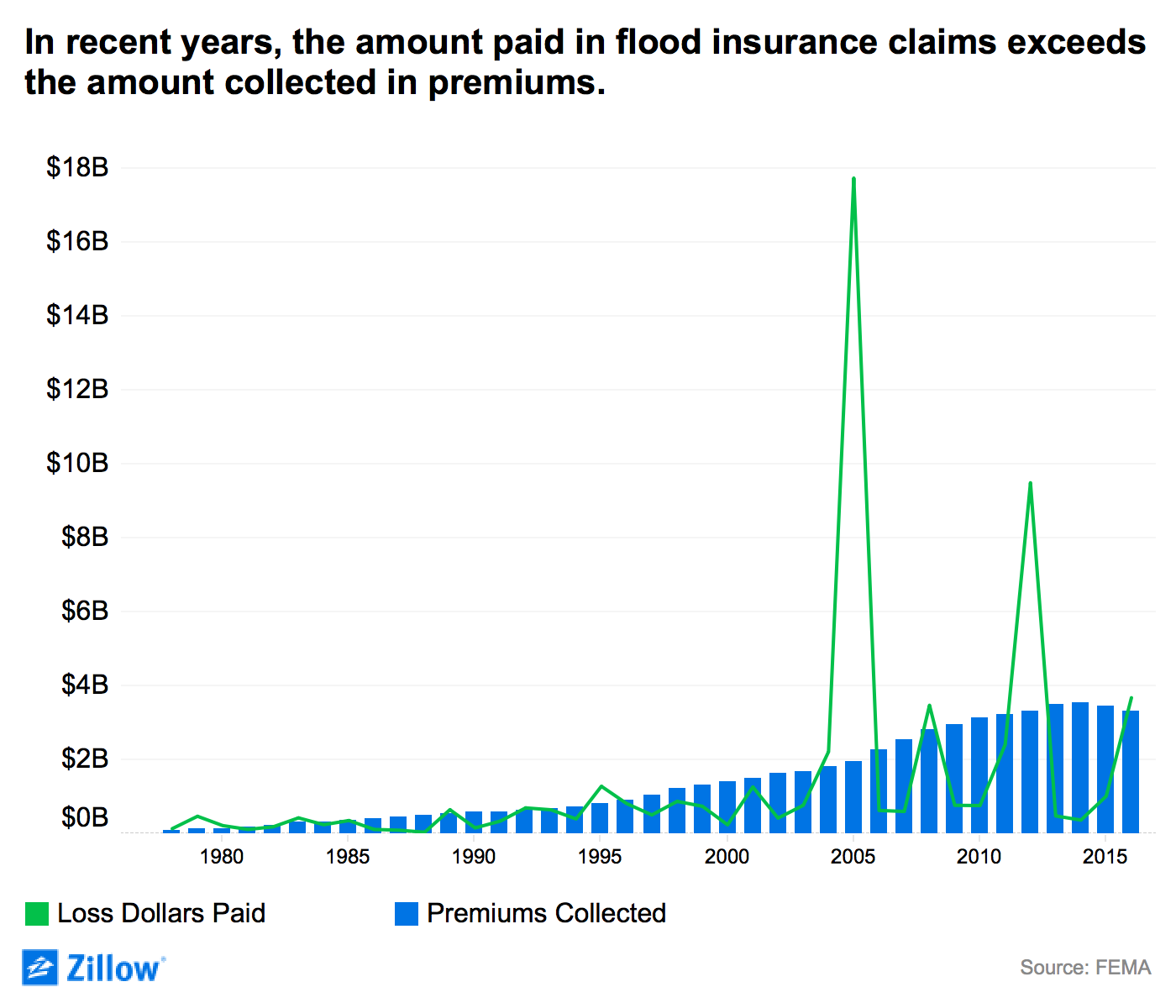

Since the NFIP began, major flood events have cost more and more as homeowners must call upon the NFIP increasingly often.

Does that create a problem?

The bottom line is the program was about $25 billion underwater before this season’s storms pushed it to its debt limits, prompting Congress to bail out the program by forgiving $16 billion in debt. A subsequent round of borrowing sent the program’s debt above $20 billion. While the money borrowed from the Treasury is supposed to be repaid with interest by premiums from NFIP policyholders, the debt has been growing since Hurricane Katrina. The Government Accountability Office reports that FEMA is unlikely to be able to ever repay its debt.

The reasons the NFIP fell into the hole are numerous (this isn’t an exhaustive list):

- Subsidized insurance may increase flood risk as buyers knowingly invest in risky property, banking on an insurance payout when the floods inevitably come. When the premiums undercharge for the real risk, development can cheaply sprawl into floodplains and put more folks in harm’s way.

- We don’t always know the true risk, because FEMA’s flood maps aren’t always accurate. A recent report from the Department of Homeland Security found that FEMA “needs to improve its management and oversight of flood mapping projects to achieve or reassess its program goals and ensure the production of accurate and timely flood maps.” Many of these maps are outdated, and as a result, the same reports found only 42 percent of maps adequately identify the level of flood risk. Even when the maps are up-to-date, they can fail when tested by a real flood. Some experts blame the inability to properly judge flood risk on increasing development and inadequate green drainage space.

- Floods hit the same areas over-and-over, and the program allows homes to remain in those areas. NFIP has routinely bailed out more than 30,000 “repetitive loss properties.” Homeowners in these situations can be stuck in a loop of flooding, insurance claims and repairs. The resale value of their homes depends tremendously on the promise of NFIP payouts, and if the bailouts cease, it could trap families without the means to sell and move to higher ground. For individual homeowners, it can actually make sense to keep rebuilding given their alternatives, but for the NFIP program as a whole, a system where 25 percent to 30 percent of claims come from 1 percent of properties isn’t optimal.

- The basic math for the NFIP doesn’t square as long as a significant number of grandfathered properties are paying premiums below what is actuarially sound. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), about 1 in 5 properties insured by the NFIP pay premiums that are lower than the expected cost of flood damage, and the average subsidized premium is about 60 to 65 percent of the cost of properly offsetting flood risk. FEMA attempts to offset the discounted premiums, but the CBO found the cost of grandfathered rates are about $300 million more than the surcharges intended to offset the discounts.

- Enforcement can be weak. A 2006 study commissioned by FEMA estimated nearly 1 in 4 properties across the nation didn’t purchase the mandatory flood insurance they were supposed to. A subsequent analysis found even lower rate of compliance with the mandatory coverage requirement in New York among homes affected by Superstorm Sandy.

- This will get worse before it gets better. Our research shows that as sea levels rise, increasing numbers of homes will be at risk. And as cities grow and natural flood barriers like wetlands are developed, we run the risk of substantially increasing our exposure to flooding.

How can we fix it?

Policymakers could scrap it completely. Some people argue that flood insurance is not the responsibility of the government, but if the ability to afford private flood insurance becomes a prerequisite to safely owning property in flood zones, then existing residents may be stuck in a pickle – deciding among a risky living arrangement, unaffordable premiums and difficulty finding a buyer should they chose to move.

Congress could reauthorize the existing laws, bail out the program with taxpayer money by forgiving its current debt to the Treasury and wait for the discounted rates of grandfathered properties to fully phase out. However, this could just be throwing good money after bad.

Congress could tweak some rules but keep the program more or less the same. These tweaks would likely aim to meet one or more of the following goals outlined by the CBO:

- Improve financial stability: Increase premiums broadly, reduce discounts, or raise rates on certain types of properties (e.g. second homes, newer construction, expensive homes)

- Better match flood risks with insurance costs: Reduce subsidies or adjust premiums to more accurately reflect risk to specific properties (e.g. new mapping technology, buyouts for “Severe Repetitive Loss” properties).

- Maintain affordability: Target discounted insurance to lower-income households based on income or use more taxpayer funds to pay claims and reduce the burden of premiums.

Are fixes coming soon?

The program is due for reauthorization by early December, 2017. On November 14, the House passed the 21stCentury Flood Reform Act, which would reauthorize the NFIP for five more years and curtail Uncle Sam’s involvement in flood insurance. Here are some of highlights:

- Encourage growth of a private market for flood insurance by removing several regulations.

- Limit premium increases for some existing policy holders and provide financial assistance for low-income households through a state-run affordability program.

- Accelerate the rate of increase in premiums for some properties with grandfathered rates, and increase some surcharges.

- Deny coverage to some properties where cumulative claims exceed payment limits.

- Deny coverage to owners of new properties constructed in known floodplains, and deny coverage for some homes with high replacement costs.

- Increase premiums for any grandfathered “multiple-loss properties” at a much faster rate than current law, or require actuarial premiums following a flood claim for “multiple-loss properties.”

- Make grants for flood mitigation

The White House recently endorsed the House’s Flood Reform Act, but lobbied for additional measures to expand private flood insurance and phase out federal flood insurance for new-construction properties.

The House bill didn’t garner unanimous support, with most Democrats and many Republicans from coastal districts clashing with the committee on concerns about premium affordability and repeatedly flooded properties. These same tensions are likely to linger as the Senate negotiates their own NFIP authorization bill before requiring a vote in the coming weeks.