By Helen Lyons posted Feb 22, 2019 on dcist.com

The structure in Montgomery County is often mistakenly referred to as “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

Less than ten miles outside the District leans an old cabin whose logs, cracked and sunbleached, date back to the 1850s— to wagons and one-room schoolhouses. To telegraphs and trains. To industrialization and urbanization. To American slavery.

Many who pass by the squat structure, which until recently bore only a small, unassuming placard to proclaim its designation as a historical landmark, mistakenly point it out to friends as “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

But Uncle Tom was a fictional character in a Harriet Beecher Stowe novel. Reverend Josiah Henson, a slave who escaped from the plantation where the cabin sits, was real—and his autobiography did inspire Stowe.

The surrounding park is now named for Henson, as Montgomery County works to honor his remarkable legacy with a new museum at the site.

Still, he never actually lived in that cabin.

The county purchased the entire property for $1 million in 2006, believing that the old structure was Henson’s home during his enslavement. But after spending another $1 million to expand and study the historical site, it was discovered that the logs date back to around 1850, over a decade after Henson left the United States for Canada.

“I think the significance of the structure is really not the point,” says Casey Anderson, the current chair of the Montgomery County Planning Board. He wasn’t around at the time of the purchase, but despite the “overstated” claims about it being Uncle Tom’s cabin, he doesn’t believe the acquisition was a mistake.

“It was certainly a worthwhile purchase. Josiah Henson is an incredibly inspirational figure and his life is a compelling story on its own,” Anderson says, noting that while Henson didn’t live in that specific cabin, there’s no doubt he was enslaved on the plantation where it sits.

The county is now building a museum to honor Rev. Henson, an abolitionist of international acclaim who was “as famous as as Frederick Douglass in his time,” according to Jamie Kuhns, senior historian for Montgomery Parks.

Kuhns has spent the last ten years writing a book chronicling Rev. Henson’s life, from his birth into slavery in Maryland to his escape to Canada in 1830.

“When we talk about famous African Americans who had an impact on the abolition and Civil Rights movements, when we talk about Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, he’s on the same level,” says Kuhns, whose book was released this month. “He should be in the conversation.”

Rev. Henson was an abolitionist, an author, and a conductor on the Underground Railroad, and his life and writings are believed to have served as inspiration for the title character in Stowe’s famous novel. Still, historians like Kuhn shun the conflation of the man with the myth.

“A lot of people don’t know that he was a real person,” Kuhns says. “People still want to call him Uncle Tom. That word has a lot of history to it. Originally that was referring to a fictional character in a book. Today it means something completely different than what Stowe envisioned or the man Henson truly embodied. It evolved over time into a slur, and so to connote Henson to Uncle Tom is just wrong.”

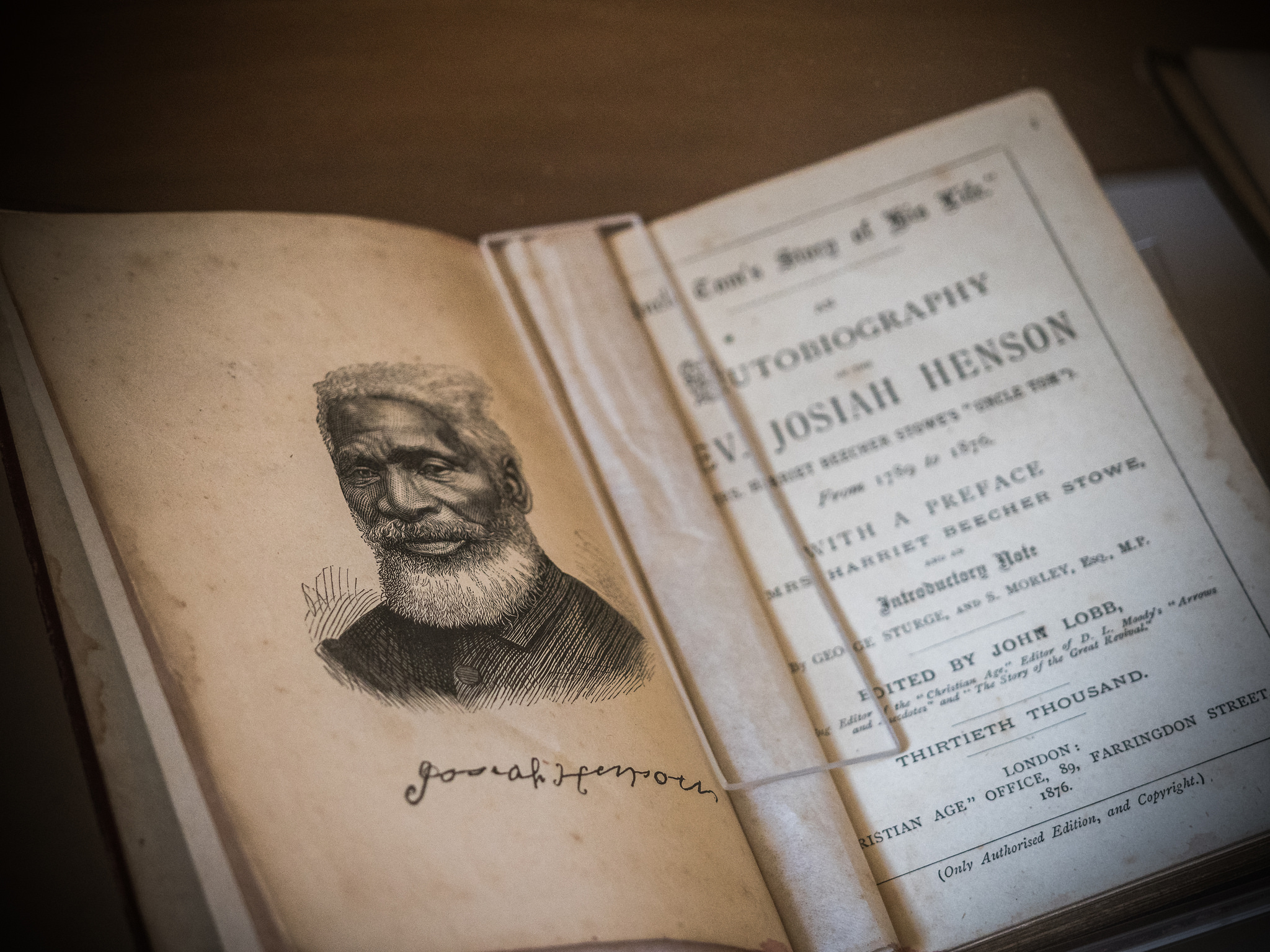

Re. Josiah Henson wrote an autobiography that was among the accounts of slavery that Harriet Beecher Stowe drew inspiration from.Tony Ventouris / Courtesy of Montgomery Parks

Rev. Henson was enslaved along with 22 others on a farm in Montgomery County.

“Sharp flashes of lightning come from black clouds, sprightly words of wit come from those who live in dark hovels, and bright gleams of intelligence come from children brought up in the most abject ignorance of books,” he would later write, and Henson saw no shortage of black clouds and dark hovels in what is now Northern Bethesda.

Henson’s father once stood up to a slave owner and was given a hundred lashes in return, then had his ear nailed to a whipping post and subsequently severed. Rev. Henson and his family members were sold to various slaveowners and separated from one another when he was a child.

Henson would rise in status as a slave on Isaac Riley’s farm, eventually becoming a trusted supervisor of Riley’s plantation.

After years of service, Henson was tricked into believing that he could buy his freedom from Riley. Instead, Riley attempted to sell him, and Henson decided the only way his entire family could become free was to run to Canada. Unlike Ohio and other northern states, Canada West, where multiple communities for formerly enslaved African Americans existed, had laws that prevented extradition.

It became a refuge for freedom seekers and Henson settled there, opening a saw mill and forming a self-sufficient and prosperous black community known as the Dawn Settlement.

“Even as he faced immense oppression, Henson had faith in himself and conviction in his faith that he could overcome tremendous adversity,” says Kuhns. “And Henson was not taught to read or write while enslaved, but he found a way to work around that hurdle, becoming a published author and a reverend well before he became officially ‘literate’ at the age of 50.”

Henson also served as an officer in the Canadian Army, leading a black militia unit in the Canadian Rebellion of 1837. He was the first black man to be featured on a Canadian stamp, and while many of Dawn Settlement’s former slaves returned to the U.S. after slavery was abolished, Henson lived out the remainder of his life in Canada.

Montgomery County is working to open a museum on the site by the summer of 2020.Tony Ventouris / Courtesy of Montgomery Parks

Building a museum to Henson’s legacy has “been a priority since I walked in the door,” Kuhn says. “Rev. Henson had major achievements. He created a church, helped establish a school where blacks could get an industrial education, was a conductor on the Underground Railroad. He met Queen Victoria twice and was entertained at Windsor Castle. President Rutherford B. Hayes hosted him at the White House.”

A master plan for the park and the building was completed in 2010, and the museum is slated to open in the summer of 2020.

“When visitors come through the house, it will not be a traditional house museum,” says Jordan Gray, the assistant public affairs manager for Montgomery Parks. “We’re using a graphic novel approach with custom art that’s very compelling, very emotional.”

Visitors will read passages straight from Henson’s own narrative, including the autobiography he published that Harriet Beecher Stowe drew her inspiration from.

“They’re going to learn about the entire enslaved community that lived here,” Gray says. “Artifacts have been unearthed that tie back to the Antebellum period. They’ll be inside, they’ll be outside.”

Casey Anderson believes the museum will do more than just educate visitors.

“This project has power and resonance that goes well beyond the Uncle Tom’s Cabin story,” Anderson says. “One of the things that’s powerful about that site for me is that it’s a reminder of the institution of slavery and that story of our past right here in Montgomery County. It’s a location that’s currently developed as part of the inner-ring suburbs of Washington, D.C. and it reminds us what happened right here, in our home, not so long ago.”

The museum will open in summer 2020, and the book that was born of Jamie Kuhn’s research is out this month.